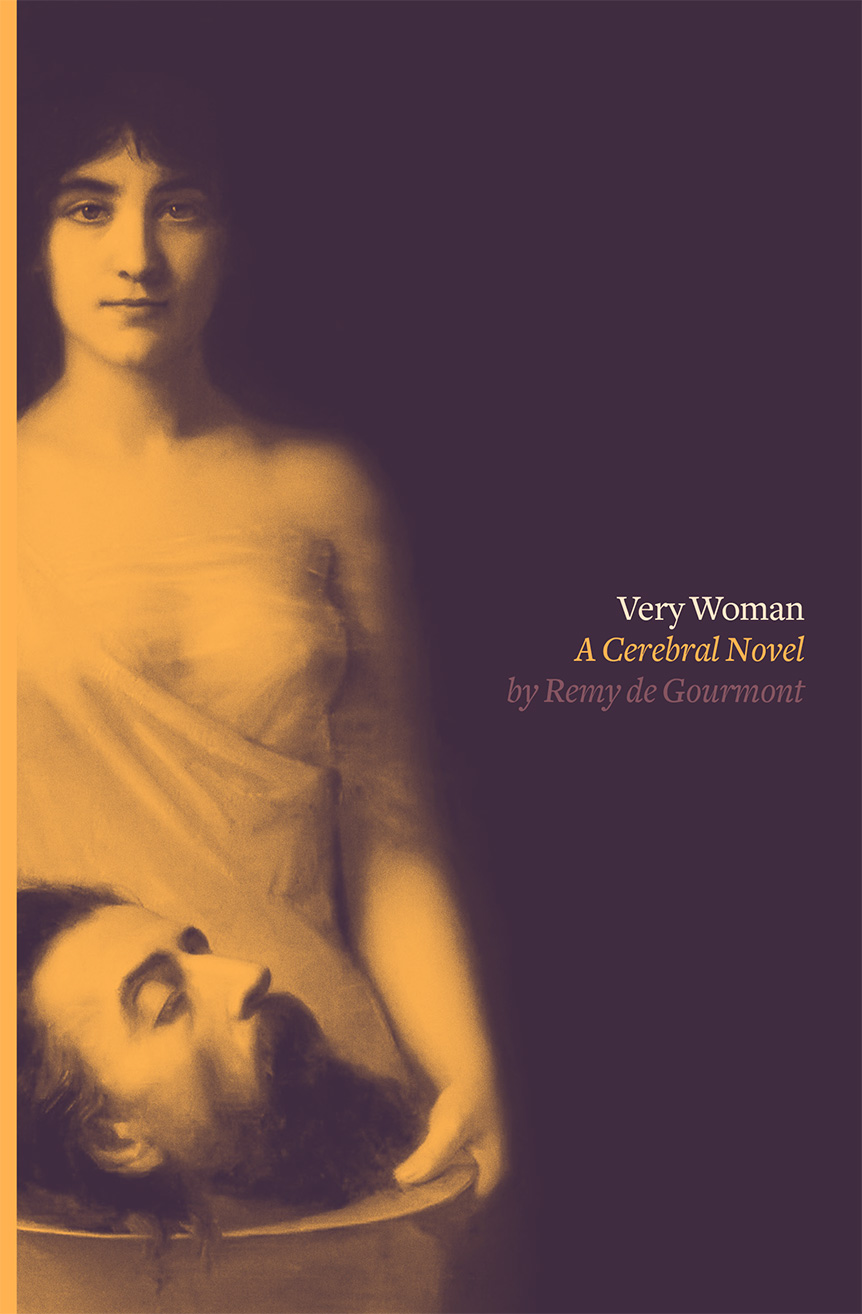

Very Woman

A Cerebral Novel

“What is that cloud, called Sixtine, which comes to trouble my royal indifference and to conceal my sun—death? I do not want to go to sleep in the shadow of her beauty. . . .”

Hubert Entragues, aesthete and litterateur, conceives a passion for the ethereal Sixtine in this “cerebral novel” of 1890. The romance remains largely imaginary, a pursuit localized in the skull of the intellectual Entragues. Alone with his thoughts and his literature, his baroque reflections careen from lyrical exaltation to sullen despondency according to the inscrutable actions of his elusive inamorata. In his refined loneliness, his lucid and sensual daydreams develop into a story within the story, mirroring and embellishing the inner experience of their author.

Very Woman is a masterpiece of the symbolist movement of fin de siècle literature. A brilliant stylist, Gourmont’s luxurious, poetic prose is full of erudition, irony, and eroticism, creating an atmosphere all its own.

“A book that meant a lot to me is Sixtine, Remy de Gourmont.”

—Blaise Cendrars

- The Dead Leaves

- Madame du Boys

- Travel Notes

- Reflections

- More Travel Notes

- Dream Figure

- Marcelle and Marceline

- The Transparent Curtain of Time

- The Promenade of Sin

- The Unleavened Dough

- Diamond Dust

- The Adorer

- Christus Patiens

- The Faun

- The Carnal Hour

- The Ideal Bees

- The Adorer

- A Complete Woman

- New Suggestions

- The Twenty-Eighth of December

- The Mystic Bark

- The Simoniac

- The Adorer

- The Color of Marriage

- Departure

- The Adorer

- The Education of Maidens

- The Aesthetic Thrill

- Pantomime

- The Man and the Pretty Beast

- The Infamy of Being Happy

- Intoxication

- An Evening in Society

- Poetic Rapture

- The Adorer

- Anger

- The Adorer

- Pride

- The Key to the Coffer

- Ultimate Peace

1. The Dead Leaves

When Nature produces these masterpieces, she rarely offers them to the man who could best appreciate and be worthy of possessing them.

—Kant, Essay on the Beautiful

They walked side by side, under the gloomy old firs whose heavy branches leaned towards the yellowing lawn.

Countess Aubry, with her charm of a negotiator of worldly loves, had just hastily brought them together, as though they were predestined for each other.

They were slightly acquainted already. They remembered having met during the past winter in the Marigny Avenue Salon, that haunt of miscarried glories, and, during the past week that they had been staying at the Château de Rabodanges (among several invalids of distinction) they had succeeded in exchanging a few vaguely suggestive words, a few affected witticisms, not without disdain for such a vain communion.

The one knew that Madame Sixtine Magne, a widow, had never held out her neck towards a new necklace—and believed it. The other knew that Hubert d’Entragues had dedicated himself, by inclination rather than by necessity, to the imperious craft of a man of letters. Her first impulse had been to consider him a cavalry captain, but the name captivated her, that name faded in history, so far as a pretty woman was concerned, and which a young man restored to all its freshness, under her eyes. Amorous and royal reminiscences whose auricular remembrance had remained in her head like a viol sound, like ripplings on fading silks, and suddenly with rustlings of steel—an admission with which her preciosity amused itself, perhaps, for she was very artful, through pride.

Entragues, on his side, was at the point of confessing to the young woman that she dazzled his imagination, but he would have had to tell her at the same time the origin—too fantastic not to be futile—of this wound, and he feared to have the air of inventing a tale.

“Then,” he reflected, “her mind would work, she would try to please me, forcing herself to deliberate charms. The experiment would be warped. I want to know what is in her; I want to penetrate coldly into the mysterious brambles of this sacred wood.”

A man and a woman, at the age of useful deceits, are never cold or truthful, face to face. Hubert judged himself capable of acting naturally, but where does the natural begin with a being endowed with several spare souls? Sixtine was but half duped and, from the first words, let it be perceived.

“Are you familiar with all the emotions of a return?” asked Entragues. “It is delicious and torturing. You enter, agitated and unbalanced and, in the confusion of brief thoughts, you say to yourself: ‘Can she be there! No, she is not there!’ The fear of a sudden grief has anticipated the deception: can it be that such joys are attained outside of dreams? ‘She is not there. There is no danger. What? No double lock? A night lamp? Is she there?’ Yes, she was there, asleep in her rose-colored morning-gown; she had risen at the sound of the key and, with bare feet and disheveled hair, pale with emotion, kissed your face, whatever her eyes fell upon—lips, brow, nose, beard—one arm gently entwining itself about your neck, the other trembling at first with the hesitancy of not knowing where to rest. She cried, meanwhile, like a hallucinated person: ‘It is you! It is you!’ Then she stepped back to gaze at you, seemed to doubt, saying: ‘Is it really you?’ And she coyly gave herself to you, resting on your shoulder, gave herself again with an ‘I am yours, still yours, as before!’ You are thrilled with happiness. To depart leaving tears, to find a smile upon your return, a being transported by your presence—that is a real pleasure, mingled somewhat with that necessary vanity of feeling yourself indispensable to some one. A special vanity in which the male experiences a despotic satisfaction.”

“Are you thus expected?” asked Sixtine.

“Who? I? No, but it might happen, and you see that I have felt it while talking to you. The slightest impulse diverts me from the present, the very tone of a voice rouses in me an inner activity and every possibility of life opens before me.”

“You must be wonderful at pretending!”

“Ah, Madame,” answered Entragues, “imagination does not destroy sincerity: it clothes sincerity with brocatels and rubies, places a diadem on it, but the same body of a woman is under the royal cloak, just as it is under tatters. To adorn truth is to respect it. This makes me recall those old evangelistaries that are so covered with illuminations that profane eyes seek the holy text in vain.”

“There are difficult writings,” said Sixtine.

“Divination is necessary when one cannot decipher. Have not women, the illiterates of love, all the intuitions of ignorance? Now then! if I said to you; ‘The heart feels the heart’s beating,’ you would agree. We are still taken in by some old aphorisms.”

“Nothing is so good as to let oneself be taken!”

Instantly astonished by a boldness of speech, whose precise meaning Entragues sought in her eyes, she laughed.

This purely voluntary laughter whose essence he notwithstanding penetrated, troubled him. A careful writer always on the quest for the exact word, new or old, rare or common, but of exact meaning, he imagined that everybody spoke as he himself wrote, when he wrote well. It was in good faith that he stubbornly persisted in reflecting, suddenly arrested by a disquietude in the presence of such words of conversation, habiliments of pure vanity. The knowledge of this eccentricity had never cured him of it, nor was he helped by the punishments of repeating this mea culpa after each mistake, taken from Goethe and composed for his personal use: “When he hears words, Entragues always believes there is a thought behind them.”

This greatly complicated his life and his talks, inducing considerable hesitations in his replies, but he was concerned only with literary anatomy and he loved to encounter complex minds upon whose momentary intricacies he would later throw light, by deduction.

Since the nut might be empty, he threw a pebble at the tree so as to cause several others to fall.

“It is preferable to give than to be robbed.”

“Oh!” Sixtine replied, “the sensation is quite different. First of all, not every one who wishes it, can be robbed. It is not even enough to let one’s door ajar, Monsieur d’Entragues.”

He felt that she had pronounced those last words in an insidious voice, but why? While waiting to understand, he responded:

“That itself would be quite a childish system. One usually places sentinels to guard the treasure chests and one provides locks for odd boxes. The spice in the pleasure of robbing lies in forcing, breaking, or taking a thing to pieces. True artists are repelled when there is nothing to do except thrust out the hand. But this is the most elementary ethics: no pleasure without effort.”

“You are speaking of robbers, I of persons who are robbed. You can belong only to the one, I to the other class, the class that is at the mercy of an eventual rifling. I wanted to explain that it requires more than that the door should be ajar or, in fine, easy to open, for if one perfects the fastenings too thoroughly, the risk is taken of being assured a truly uncivil security. Well, more than all this, it is needful that there be visible or suspected objects to steal; it is needful that, by appearances, by external and attractive promises, the thief be tempted.”

“You have anticipated me, Madame, in awarding yourself this personal compliment. I was about to make it. But you know, better than I do, your gifts and all that might draw curious and thievish hands to the dreamed of coffer.”

“Too much frankness and irony, Monsieur d’Entragues. You were not born a thief.”

“Alas! I have no hiding place secure enough for such larceny. My left hand would not know what to do with what my right hand pilfered.”

The somewhat brutal candor of this disinterestedness did not seem to wound her. On the contrary, she thought:

“He is no fool. Another would have thrown himself at my imprudence, would instantly have urged me to let myself be taken!”

For his part, Hubert, seeing that the nuts were decidely meaty and not too tasteless, reflected:

“I will amuse myself again with throwing a few stones at the branches.”

Sixtine forestalled him:

“What end are you aiming at? Love is too fleeting for your stability, let us admit. In that case, where does your life lead? Ah! poet, to success?”

“I am not a poet. I do not know how to cut my thoughts into little morsels that may be equal or unequal, according to the chance of the chopping knife. My prose gets its rhythm only through my breath. Only the pin thrusts of sensation mark its accents and the royal puerility of rich rhymes passes my understanding . . . .”

The vlouement of a crow’s wings agitated the air above the trees. Hubert remained silent, listening. Then:

“Vlouement, that’s it, vlouement of wings, with the v v v. Is it the v v v or the f f f? The filement of wings? No, vlouement is better. Once more, crow!”

Sixtine, a trifle bewildered, stared at him open-mouthed.

“Those damned crow wings—one cannot describe them! Oh! success! Does the apple tree solicit applause for having borne fruit? From this one could construct quasi-evangelical parables. If I am not my own judge, and if I displease myself, what matter though I please others? Who are the others? Is there in the world an existence outside of myself? Possibly there is, but I am not aware of it. The world is myself, it owes me its existence, I have created it with my senses; it is my slave and no one else has any power over it. If we were thoroughly certain of the fact that nothing exists outside of ourselves, how prompt would be the cure of our vanities, how quickly our pleasures would be purged of it! Vanity is the fictive bond which links us to an imaginary exterior world. A little effort breaks it and we are free! Free, but lonely, lonely in the frightful solitude where we are born, where we live and die.”

“What a sad philosophy, but what a proud one!”

“It contains less pride than sadness, and I would give much of its arrogance so as never to feel its bitterness.”

“Who led you to it?” she queried, interested in these matters which seemed sufficiently new to her mind.

“But it is natural. How conceive a life different from what it clearly appears to eyes that can see? Yes! perhaps a certain illusion is possible . . . . What a pity, doubtless, what a pity for me that I did not meet you earlier—years ago. I would have loved you, and then . . . .”

“What would have befallen your destiny, as a result?”

“You would have deluded me about life’s value, Madame,” Hubert continued, with a poetic enthusiasm that bordered on persiflage. “I would have drunk, like an external absinthe, the fluid illusion of your sea-green eyes and would have chained myself to life by the golden chain of your blond hair.”

She veiled herself with indifference lightly embroidered with irony and, believing herself sheltered from a too inquisitive glance, ingenuously replied:

“It is really but three years since I was twenty-seven. It is now the thirtieth year, or almost.”

He looked at her from head to foot, but without insolence.

“What frankness! But you have no need to lie.” His eyes returned to her figure, which was a little full, he thought.

“Yes, aesthetic, isn’t it?” hazarded Sixtine, negligently lifting her arms to fasten some pin to her coiffure.

The gesture was fine and instrumental in making her bust more delicate in line.

He prudently replied:

“Aesthetic? Oh, no! It seems good and with no treacheries.”

A smile, quickly banished, attested the woman’s contentment and was the most feminine efflorescence of the old human perversities. In a slow, undeceived voice, she said:

“It is lost time to wish to love me.”

“See,” Hubert returned, “you breathe on my bubbles and my sole and last chance of illusion vanishes, for in placing my desires in the past, I secretly constructed a bridge spanning the present. Ah! Madame, what transcendental cruelty!”

She was conscious of having taken a wretched crossroad, and of having become bemired there.

They spoke no more.

The shadow diffused itself in swift waves. Slightly nervous, Sixtine walked towards the light of a nearby glade, at the foot of the avenue. There, the oaks and beeches, whose foliage was already brightened by the setting sun, were grouped in a narrow grove. The wind passed, stirring the dry leaves. A low and heavy branch bent down with the sound of a rustling of stuffs. Like a drop of rain, a leaf, then many leaves, descended with a slow moaning sound.

“They follow me! They pursue me!” she cried, caught in the vortex she vainly fled.

And swept away, like a leaf in the circular flight of wind, she drew near Entragues, distracted, panting, crying all the time:

“The leaves pursue me, the dead leaves pursue me!”

“What is the matter,” Hubert asked, surprised by such a strange crisis.

While, still frantic and trembling, she seized his arm and leaned against it, he coldly added:

“Have you ever committed a crime in your life?”

This ironic interrogation changed the nature of the fever, like scalding water on a stone.

“Perhaps!” she answered, suddenly pale.

“Then you become altogether interesting.”

It was beyond her strength to retort to this impertinence. With a trembling of all her little muscles, and without knowing why she did it, she tried to pull off her gloves. When one of her hands was free, she shook it, pulled it, cracked its joints.

“Excuse me,” Entragues continued. He took a malicious pleasure in making the untuned instrument vibrate. “But is there not a stain on the little finger?”

“No, it was the poison.”

This came from her lips with the calmness of a meditated confession.

His eyes sincerely troubled, Hubert watched the monster who disengaged herself and fled, throwing these words to him as an adieu:

“I am leaving tomorrow, come to see me.”

(End of Chapter 1 of Very Woman)

This Antipodes edition is a republication of Very Woman (Sixtine): A Cerebral Novel, translated by J. L. Barrets, published in 1922. Originally published in French as Sixtine: Roman de la vie cérébrale in 1890.

ISBN: 978-0-9882026-8-9

226 pages

Antipodes books are distributed worldwide by Ingram Content Group